It’s that time of year again. Product teams everywhere are setting their OKRs and quietly wondering why this process feels harder than it should.

“Most product leaders are about to make the same mistake with their 2026 OKRs,” says airfocus by Lucid’s Head of Product and co-founderMalte Scholz. “They'll start with a spreadsheet, cascading objectives, neat trees flowing downward… but that's not reality.”

On paper, OKRs are simple: Set a clear objective. Define measurable key results. Align teams around what matters most. In reality, things are messier. Product teams operate on different cadences. Goals overlap and compete. Strategy shifts faster than quarterly planning cycles. And increasingly, PMs are expected to layer AI initiatives on top of everything else.

Recently, Malte asked his network of product leaders to share their hard‑won OKR lessons. The responses were strikingly consistent in their belief that most OKR problems don’t come from poor intent, but rather from treating OKRs as a documentation exercise instead of a strategic one.

Here are some of the top tips these product leaders shared, translated into practical guidance for PMs.

can support your team.

Book a demo

1. Start with strategy, not the spreadsheet

One of the most common OKR failure modes is starting with a template instead of a point of view.

OKRs often become a formatting exercise of cascading objectives, neatly nested key results, and colour‑coded status updates. What’s missing, though, is the underlying strategic choice.

Before writing a single objective, leaders need clarity on what actually matters in this cycle – and just as importantly, what doesn’t. A short strategy document or clear strategic narrative should come first. Only then do OKRs make sense as a way to test and operationalize that strategy.

If you skip this step, OKRs tend to default to restating what the business is already expected to do anyway. Revenue growth, retention, delivery commitments – all of which are important, but they’re not OKRs. As one product leader explained, OKRs should stretch the organization beyond business as usual, not micromanage it.

TL;DR: If you can’t explain the strategic bet behind an OKR, it probably shouldn’t exist.

2. Ruthlessly limit focus

Across the comments, there was overwhelming agreement on one point: fewer OKRs are better.

Teams with 10 or more objectives aren’t necessarily as ambitious as they are unfocused. When everything is a priority, what often happens is that nothing is. Several product leaders shared that they would rather have a single, well‑defined objective than five vague ones competing for attention.

Limiting OKRs forces hard conversations. It makes trade‑offs explicit. And counter‑intuitively, it often gives teams more autonomy. When the destination is clear, PMs have far more freedom to choose the best path to get there.

A useful rule of thumb shared by multiple contributors is to stick to two to three objectives at most. In some cases, even one business‑level objective is enough.

Focus doesn’t mean doing less work; it’s just being clear on what truly matters.

3. Don’t cascade OKRs; align around shared outcomes

Traditional OKR theory often promotes cascading objectives down the organization. In practice, though, this can do more harm than good.

Breaking objectives down by function or team tends to fragment ownership and discourage collaboration. Product work rarely fits neatly into organizational boxes. Most meaningful outcomes depend on multiple teams moving together.

Several leaders recommended using shared business‑level objectives across the organization, with teams defining their own key results based on their remit and context. This keeps everyone aligned on the same outcomes without turning OKRs into a top‑down control mechanism.

The key ingredient here is context. Teams don’t need their objectives broken down for them; they just need to understand why the objective exists and how their work contributes to it.

In other words, treat OKRs as a network of outcomes, not a hierarchy of tasks.

4. Separate OKRs from business‑as‑usual work

Another recurring theme in the responses: Not everything belongs in an OKR.

OKRs are designed for the most important strategic initiatives, not for tracking everything a team does. Trying to shoehorn business‑as‑usual work into OKRs usually leads to bloated frameworks and meaningless key results.

This is where many PMs feel the tension most acutely. Roadmaps still need to be delivered. Customers still need support. Bugs still need fixing. None of that disappears just because OKRs exist.

The solution is to be explicit. Allocate time and capacity for BAU work, and govern it through other mechanisms. Use OKRs only where there’s a genuine strategic question to answer or an outcome to move.

If every roadmap item needs a key result, your OKR system will collapse under its own weight.

5. Write specific key results that force decisions

Vague key results are another major source of frustration. “Improve customer satisfaction” or “enhance performance” may sound reasonable, but they don’t help teams decide what to do next.

Strong key results are measurable, time‑bound, and decision‑enabling. They tell you, week by week, whether you’re on track and what needs to change if you’re not.

Several leaders stressed the importance of distinguishing between outputs and outcomes. Shipping features, training models, or increasing activity are outputs. What matters is the impact those outputs have on users, the business, or the quality of decision-making.

A good key result should change a conversation, not just update a dashboard.

6. Be ambitious, but grounded in reality

Ambitious OKRs are important, but impossible ones are demoralizing.

Many product leaders highlighted the importance of striking the right balance with your OKRs. They stressed that objectives should stretch teams, but at the same time still feel achievable with focus and effort. One leader suggested aiming for outcomes that feel uncomfortable but plausible, not fantasy targets that everyone quietly ignores.

Context matters here, too. Teams need to understand the “why” behind an objective to judge how bold their key results should be. Without that context, ambition either collapses into caution or tips into wishful thinking.

The key takeaway: your ambition should create productive tension, not paralysis.

7. Set OKRs at the speed of learning, not the calendar

Fixed quarterly cadences can be useful, but they shouldn’t be sacred.

Markets don’t move on a timetable, and neither does insight. Several leaders argued that OKRs should evolve when the strategic priority changes, not simply because a quarter has ended.

This becomes even more important for AI initiatives. In fast‑moving GenAI environments, early assumptions often break. Measuring learning velocity, decision quality, or validated hypotheses can be more useful than locking in rigid numerical targets too early.

A stable cadence in an unstable environment creates a false sense of control.

8. Invest in leadership capability first

Finally, one of the most candid observations product leaders shared: Many OKR failures actually start at the top.

Leaders who come from legacy goal‑setting environments often lack hands‑on experience with OKRs. And without a shared baseline understanding, product teams inherit inconsistent expectations and conflicting interpretations.

Training leaders first – and modelling good OKR behaviour – sets the tone for an entire organization, while also protecting PMs from being asked to make broken frameworks work.

OKRs succeed when leaders use them as a thinking tool, not a reporting layer.

OKRs are a product decision, not an admin task

The common thread across all the responses from product leaders was that OKRs work best when they reflect reality.

They should capture your strategic intent and embrace interconnected work, but also be able to evolve as teams learn. When treated as static documents or reporting artefacts, they quickly lose credibility.

For PMs, the challenge is using OKRs to make better decisions, faster. And that starts by designing OKRs for how product work actually happens, not how we wish it did.

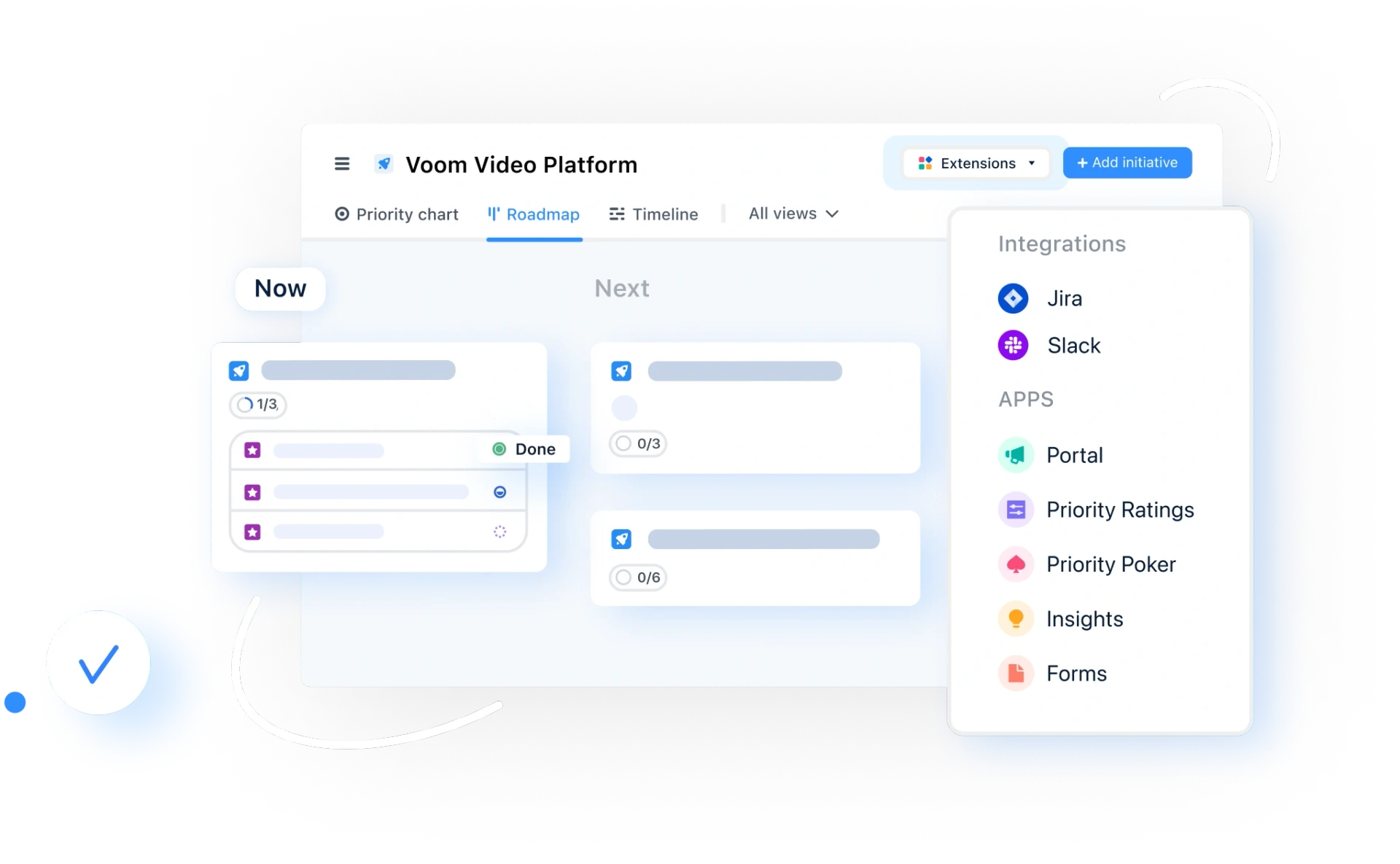

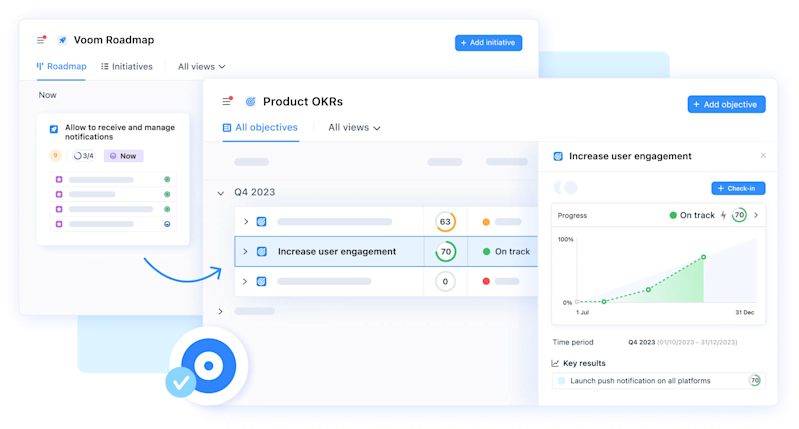

Supercharge your product strategy: OKRs built into your product management platform

airfocus lets you manage your OKRs and connect them directly to your roadmaps and workflows. Get all your product artifacts in one place to understand your teams' progress at every level, from a single user story to your long-term company objectives.

Why does this matter? By linking all your airfocus items to key results, you ensure the day-to-day product work stays on track with your overarching objectives.

Explore airfocus’ Objectives & OKRs software and bridge the gap between strategy and execution.

Emma-Lily Pendleton

Read also

Experience the new way of doing product management

Experience the new way of doing product management