Product Lifecycle

What is the Product Lifecycle

Definition of the Product lifecycle

The product lifecycle is the journey each product takes from the inception of an idea all the way through to a product’s retirement.

Typically, the product lifecycle is understood to consist of the following stages:

Development

Introduction

Growth

Maturity

Decline

Conceptualizing a product lifecycle in this way is important because, at each stage, a product is met with different challenges, risks and opportunities.

In order to meet challenges, reduce risks and take advantage of opportunities, relevant strategic decisions need to be made at different points in time. These decisions could be about marketing, pricing, distribution, sales, product support or feature development etc..

There is no hard and fast rule about how long it takes for a product to graduate from one lifecycle phase to the next. How long a product spends in each stage, and how long the product lifecycle is in total, will vary enormously depending on the product and industry.

That said, there are clear defining features of each phase, which can be understood in the following way:

1. Development

No matter how basic it may be, every product will require some element of development to get to a launchable MVP.

This early development period can often be a difficult time, as it draws on resources without any corresponding revenue. If you already have a successful business, this means reinvesting revenue from other profitable products to cover initial costs. Or, in the startup world, this is typically the point when entrepreneurs tend to carry the investment strain on their own shoulders, by working without pay or on limited funds.

This development period is often known as the ‘valley of death’, where products try to bridge the gap from development to commercialization.

2. Introduction

The next step in the product lifecycle is the introduction phase starts when your MVP (minimum viable product) goes to the market for testing and iteration. This is a volatile period where many fundamental elements will be defined, for example:

How to position the product from a brand and pricing and perspective

Which messaging hooks resonate with your target audience

Which marketing channels offer the biggest return on investment

Feature lists that should be built into the backlog

The introduction phase is still a very uncertain time, while you may be generating some revenue, profitability is likely to be a long way off.

3. Growth

By the time the growth phase is reached in the product lifecycle, it will have a clear product-market fit with proven adoption and traction. Your focus will now be on increasing market share, and you can be looking towards profitable operations.

The nature of your marketplace is likely to determine price points at this stage. If you have a product with relatively few competitors, you may decide to go to market at a premium price point.

Or, as is much more commonly the case, you may choose to forgo profitability in pursuit of acquisition and brand awareness. Typically this will be done by offering significantly reduced pricing and other promotional activities for early adopters.

During the growth phase, you are likely to invest significantly in marketing spend to maximize potential reach.

4. Maturity

A product is considered to have reached maturity when growth and rapid early acquisition begins to plateau.

During this phase your primary focus will be to shift from acquiring new customers, focusing on retention as a core metric instead. Sales and marketing will likely become less of a priority as you begin to invest more heavily in customer success mechanisms, such as support teams, online account areas, and any other elements that may impact how ‘delightful’ your products are to use.

At this time, you may also look to develop supplementary products or services as a way to increase revenues from existing customers.

5. Decline

All great things must come to and end, and when this applies to a product we call it the ‘decline phase’, the final stage of the product lifecycle. During this period, competition is high, consumer needs are likely to be significantly different to when you launched the product, and revenues are almost certainly diminishing.

Decisions now need to be made about whether to terminate (sunset) the product, sell it, or try to give it a new lease of life by investing in new feature development.

Benefits of the product lifecycle model

The main benefit of the product lifecycle model is that is allows management to determine what strategies they should be using. Ultimately, the aim of this is to extend the profitable lifecycle of a product.

Of course, every product’s success will ebb and flow, however some common strategies to extend profitability are:

Advertize: to increase market awareness and bring in new business

Reduce price: to become more attainable, to more customers

Add new features: to become more applicable or attractive

Enter new markets: to increase the potential market size be entering new locations or segments

Refresh the brand or improve the experience: to maintain excitement and interest

Challenges of the product lifecycle model

No two products are ever the same in nature, and no product will pass through a ‘standard trajectory’.

The product lifestyle model can, therefore, be problematic when teams assume that they can simply use it as a blueprint of the tactics to employ at different points in time.

Instead, product teams and strategists should think about the product lifecycle as something that they proactively influence, rather than simply respond to.

For example, you may decide its strategic to to extend the growth stage in order to maximize market share to support a new feature release, or to prolong the maturity stage to fund the development of a new product.

There is also no reason for a product to necessarily pass through all five stages. Many products may go straight from growth to decline as a result of an unexpected change in the market.

Other products may simply buck the trend of what’s typically expected in this model. Tech products especially have the potential to grow exponentially over a short period of time, while not attaining profitability until well into the maturity phase.

This means that many millions could be invested in an app that gains huge traction, and at a point where the traditional lifecycle model would expect a profit to be made, the business is still making a loss. Uber could be considered a classic example of this.

General FAQ

Glossary categories

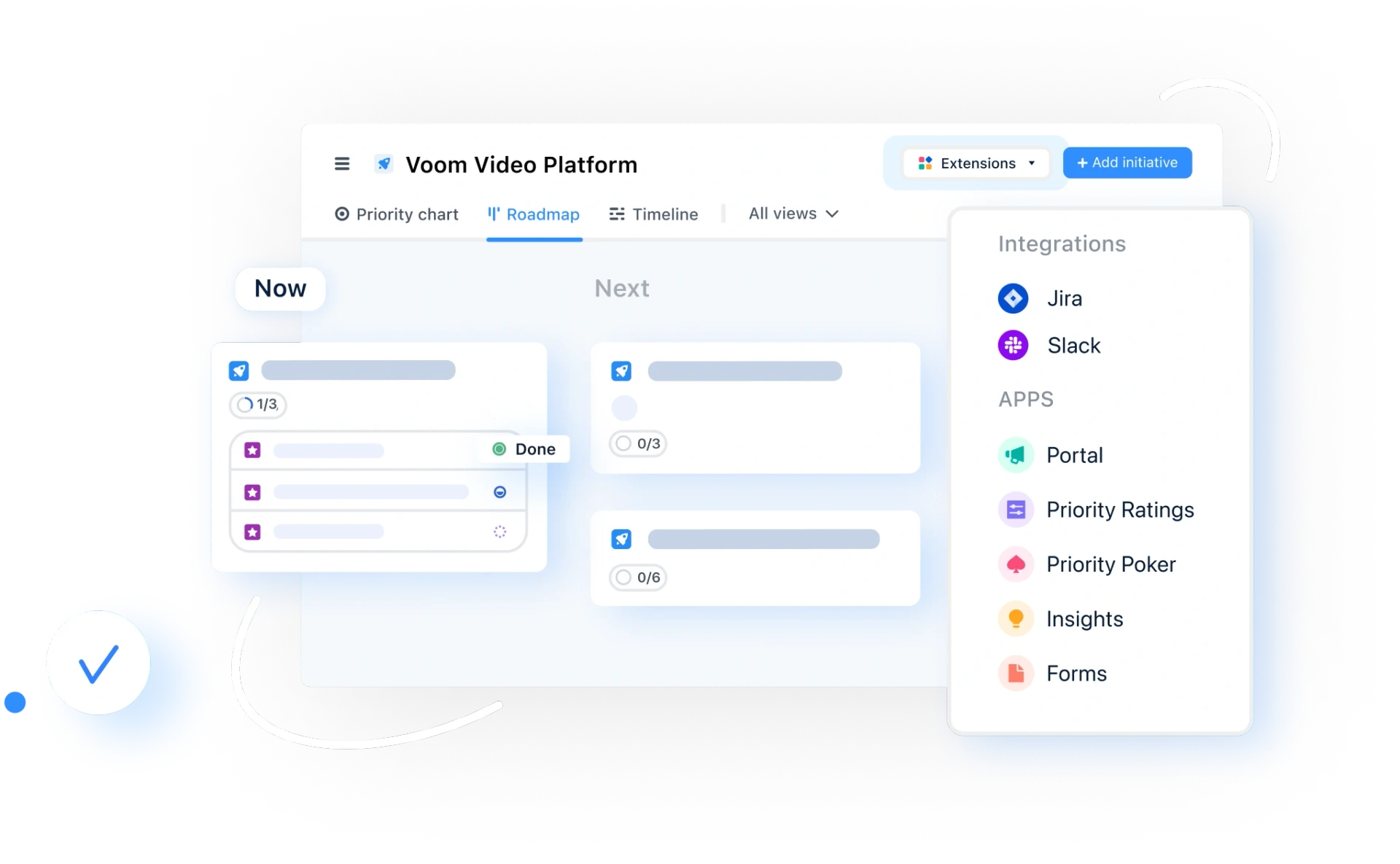

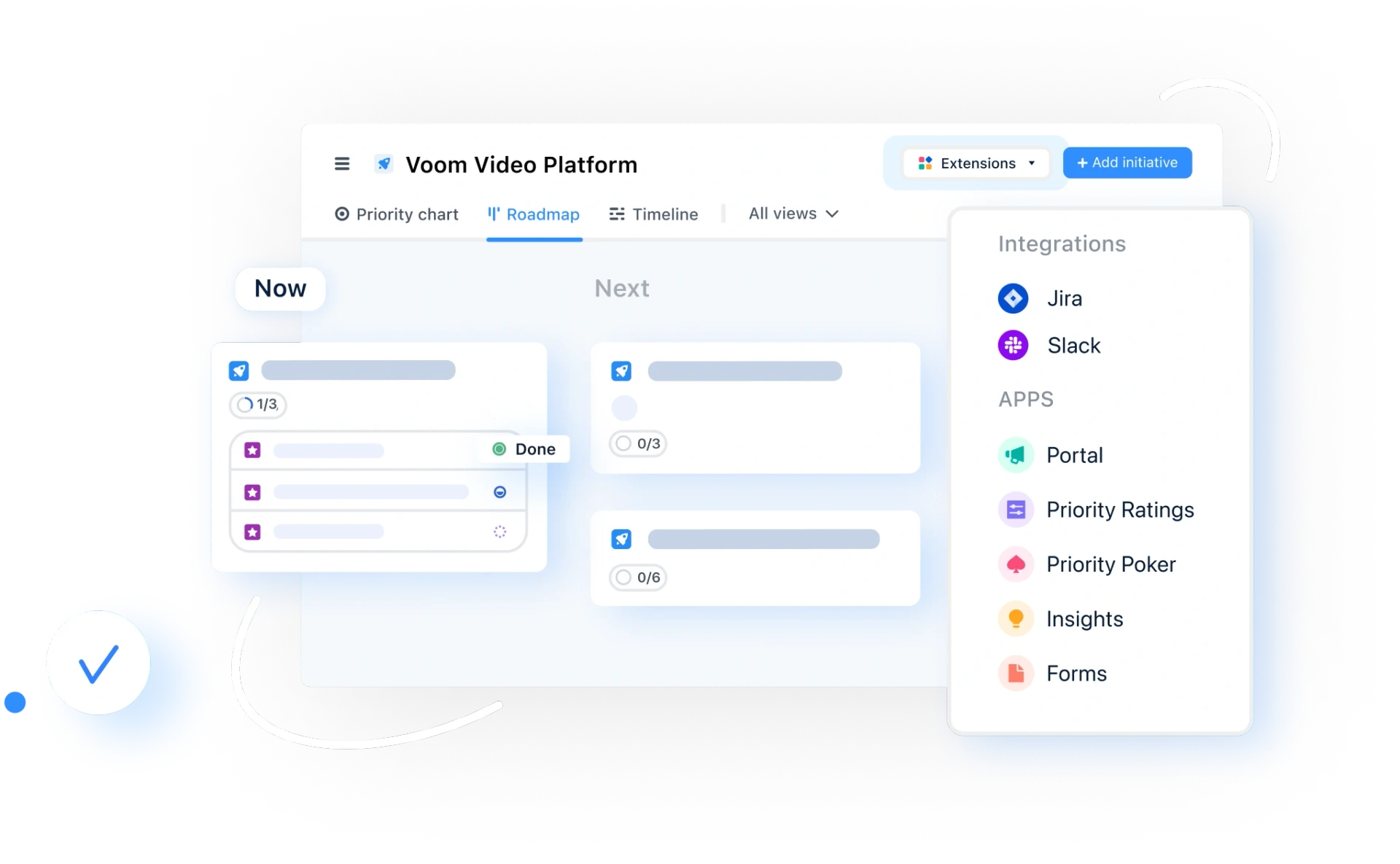

Create effective product strategy

Experience the new way of doing product management