Sunk Cost

What is sunk cost?

Definition of sunk cost

Money that has already been spent and cannot be recovered is a sunk cost. The sunk cost phenomenon in business is a product of the idea you need to "spend money to make money." A sunk cost in product management could include marketing, new software, equipment, research, or facilities expenses.

Not all fixed costs are sunk costs, but all sunk costs are fixed costs. Sunk costs are specifically costs that can’t be recovered. For example, equipment is not a sunk cost if you can resell it or return it.

And sunk costs don't just affect companies — they happen in everyday life too. Let's imagine you spend $50 on a theater ticket but can’t go at the last minute. Your $50 investment would be considered a "sunk cost" and wouldn’t influence your decision to purchase theater tickets in the future.

So, what are some common examples of sunk cost?

For one: equipment. Office equipment, like printers, often need replacing after a few years. At this time, the money spent on the old equipment is deemed a sunk cost.

Sure, some of it may be recovered if you can sell off some parts. But all the money that was spent on it initially is sunk.

Or, let’s say a SaaS company invests in usability testing for a new platform feature. After launch, the feature is largely ignored by users, and no additional sales resulting from the development.

In this case, all the money invested in researching the feature would come under sunk cost. And, in this instance, the worst thing you can do is pile more money into trying to reverse the financial loss — a mistake known, to some, as the sunk cost fallacy.

What is the sunk cost fallacy?

Because business leaders can be risk-averse in their decision-making, many fall foul of the sunk cost fallacy — that is, the belief that further investment will eventually reverse the losses from sunk costs.

Looking at our SaaS company, with the failed new platform feature: they may think that researching and adding further features will eventually lead to them recouping the sunk cost of the initial research.

This is not the case. The money initially spent is gone — sunk — and should not be factored into future decisions.

The best course of action would be to realize that customers like the platform the way it is and not risk increasing the sunk cost of researching further, unwanted additions.

What is an example of the sunk cost fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy is the desire to continue doing something based on how much time, effort, or money you invested. So ordering too much food at a restaurant and forcing yourself to eat it all just to “get everything you paid for” is an example of the sunk cost fallacy.

Let’s consider a product that’s already spent all its budget, and senior management wants the product manager to avoid overspending. If the project has already spent its $1000 budget to develop a product and it only needs $100 more to be able to release to market, it would seem like a simple enough solution to all the extra $100. But if that additional $100 will only add a feature to your product that your competitors already offer, it might not be worth the investment. If you spend the extra $100, you increase the overall investment but haven’t actually improved the product.

Avoiding the sunk cost fallacy in product management

The sunk-cost dilemma involves deciding whether to continue a project with a significant sunk costs or abandon it entirely. Money that has already been spent or that has been formally committed to be spent is known as sunk expenses. And those expenses are gone.

So abandoning a product can have serious financial consequences, and knowing how to avoid sunk costs is important. But, knowing when to cut your losses is a sign of maturity in product development, and it’s something that even the most seasoned product manager struggles with frequently. Here’s what you should do:

Lower the cost you sink: Avoiding the sunk cost fallacy in the first place is a great approach! According to lean principles, we should only invest the bare minimum necessary to create a product that will be useful for assessing our future investments.

Don’t overthink: Overanalyzing is pointless. Spend less time researching and planning and more time acting. Unsurprisingly, experience is a better teacher than imagination.

Take others into account: Listen to the people around you. We often get too close to the things we’re working on, which clouds our judgment. If your team or stakeholders think you shouldn’t be continuing a project because of all the work and money you’ve invested, they’re probably right. That’s why cross-functional teams bring together experts from product, design, and engineering. The more opinions you have, the better your decisions will be.

General FAQ

Glossary categories

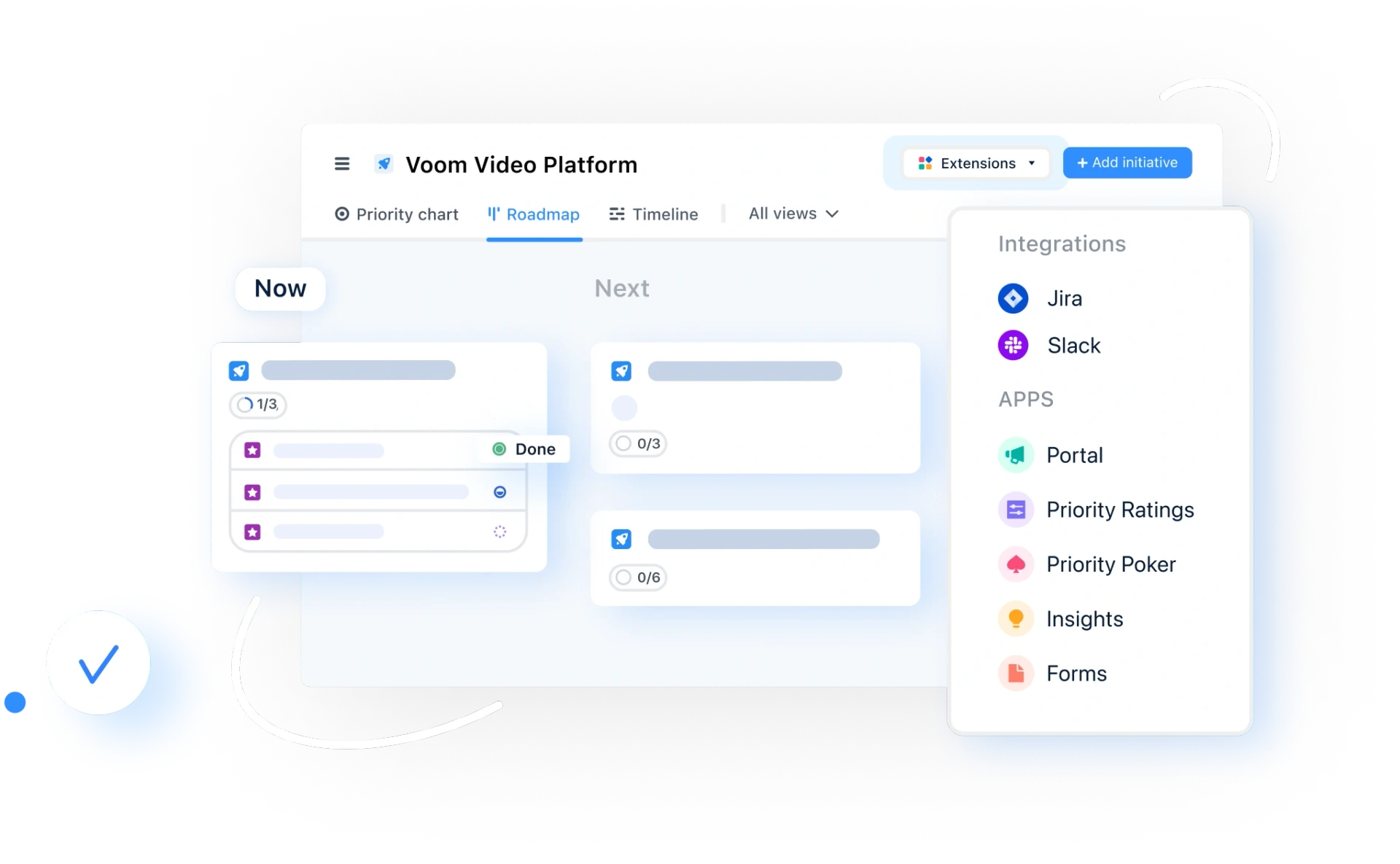

Prioritize with confidence

Experience the new way of doing product management