The soul of product ops: 4 Lessons Graham Reed learned building product ops teams from scratch

Graham Reed fell into product operations before he even knew it had a name. What drew him to it? The absence of a dedicated team to focus on the craft of product management. This gap becomes increasingly evident as the world gets busier and product managers are expected to deliver more, better, and faster. “There's absolutely no time to look inward and think, how could we be doing this better?” he says.

Graham is the Head of Product Operations at HeliosX. Beyond his role there, he co-hosts the award-winning Product Opscast, co-founded the product ops knowledge hub Product Ops Confidential, and frequently speaks at global industry events such as PLA London and Product Weekend. Building product ops teams from the ground up in five businesses has shaped Graham’s perception of what this discipline is really about. Join us as we unpack the valuable lessons he’s learned over the years.

Communication is key, but so is understanding how the business operates

A big part of effective product operations is facilitating communication and knowledge sharing within product teams and across departments.

Graham Reed acknowledges, “Something that I've always been very successful with is providing good communication frameworks. How do product teams communicate? How do they share information?” He’s leveraged that skill in many product ops projects, “I've built what I call ‘product hubs’ in every one of those businesses before. It's a central location for sharing information about what we're building, when it's coming out, and how you can find out more about it.”

The surprise came when Graham joined a new business to develop a product ops team and rolled out one of those product hubs, only to find out that it was incredibly underused. “We're a business of nearly 2,000 people,” he explains. “But, of those 2,000 people, we have about 400 people in the warehouse. Another 600 are customer service agents. So, actually, half of the business will never even interact with product.”

The lesson was clear for Graham: “The trap I've fallen into is assuming that businesses should be communicating left, right, and center, and that every part of the business is equally interested in what’s being shared – and the reality is, that’s not the case.” Reflecting on the consequences of this, he states, “It's a wasted effort for everybody that's contributing to that. Does this have material value? If not, let's focus on something else.”

So, what was the alternative? “We're going TikTok-style with short update videos produced as different teams see fit, that still allow for async consumption, but with targeted information for specific audiences, from operators to senior leadership. A library of shareable, specific assets, pushing that to audiences rather than expecting them to be curious and discover for themselves.”

The bottom line is, in Graham’s words, “There is no blueprint.” No two businesses are equal, so there is no guarantee that a communication framework, however powerful, will work for one as it does for another. One must deeply understand how a specific business truly operates, including its internal structures, employee roles, and actual communication patterns, before implementing solutions.

Mind the bureaucracy trap

The role of product operations is to oil a product team’s engine, not add sand to it. To Graham, it all comes down to asking, “How do we embed these ways of working and these habits so that people don't even notice that they're doing them?”

However, the truth is: Product ops teams can be mistaken for the process police when they fall into the bureaucracy and overengineering trap – and Graham has been there. He has found himself, at times, “trying to solve six problems with the same tool, and not managing to solve any of them particularly well.”

Years of experience in product ops have taught Graham how to avoid these pitfalls. He says, “A lot of that is down to my interaction with the product managers, or any of my stakeholders, up and down the chain.“ The key is making sure that his stakeholders know and feel that he’s on their side. “I need to understand what they want and what they have now; get the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

This understanding must be shown with actions, and Graham has found the solution that works best for him: Holding “very honest, informal, feedback sessions with stakeholders where I ask them what’s working, what’s not working, what areas I’ve missed, where I’ve overengineered.”

The point here is that product ops is about embedding healthy habits, not forcing rules. And for that to happen, you have to get closer to product teams, understand what’s blocking them, empathize with them, and eliminate that friction. Don’t forget that the main goal of product operations is to enable product teams to do their best work.

Bridging gaps and building trust

A common challenge product teams face is the gap between them and the C-suite, and it usually stems from a lack of information. “There is often a gap in sharing what we’re working on, and why we’re working on X versus Y,” says Graham. But even when they understand why certain projects are being prioritized, they might not have the full picture: “They want to understand, ‘What's the end goal? We're going to work on this, but why? What's this going to look like in 12 months' time?’ They need us to paint the picture of the journey that we’re on.”

This proves Graham’s first point that communication is one of product ops’ key components. “The challenge is making sure that our product teams are supplying the right information to leadership.” Graham brings a concrete example of when he directly asked a C-level executive, �“What’s missing for you? Do our product teams show the value of what they’re doing?” Bringing up these questions allowed him to work on a system that would provide the right information systematically.

Bridging the information gap entails having the right, and sometimes hard, conversations. Those discussions should sound something like, “Okay, that's an interesting direction. Talk me through more of that. Have we considered this? And why haven't we considered this?”

What’s at stake when these conversations are overlooked? Trust in the product team. “There’s an element of trust, not in the people and their abilities, but in whether we're working on the right things,” Graham says. “When we start to show that process, when they understand how our team's working, they will become much more comfortable, and I've seen this in so many businesses.”

Change management is personal and long-term

What’s something Graham’s experience in product ops proved him wrong about? “The belief that everybody should want to be better, that everybody should want to improve.” He used to think, “Why wouldn't you? If you can be faster, or more efficient, or save time, why wouldn't you want to?” After years of building product ops teams 0-1, he realized “the huge amount of personality and emotion that sits behind the will to change.”

“A big part of product ops is change management,” Graham explains. And while some colleagues might always be up for trying new things, you’ll also cross paths with people who would rather keep things as they are. There are valid reasons to resist change. “Maybe it's just working for them right now. Or maybe they want to see the value before they engage with it.” Making product operations successful entails understanding that some people may take longer than others to adopt certain shifts.

Product ops demands exceptional people skills and sensibility. “It's a role that requires maturity. Not age maturity, but mental maturity.” This realization has led Graham to think carefully before bringing someone new to the team: “When I'm hiring people for product ops, the first thing I try to ascertain is how mentally prepared, robust, and mature they are.”

Graham Reed’s experience underscores one simple truth: There is no universal blueprint for success. Effective product operations hinge on a thorough knowledge of a business's unique intricacies, communication patterns, and employee roles. It's about facilitating – not dictating – and building trust through honest feedback and engagement. The key to that is empathy – seeking to understand people’s personalities, motivations, goals, and ambitions.

Francisca Berger Cabral

Read also

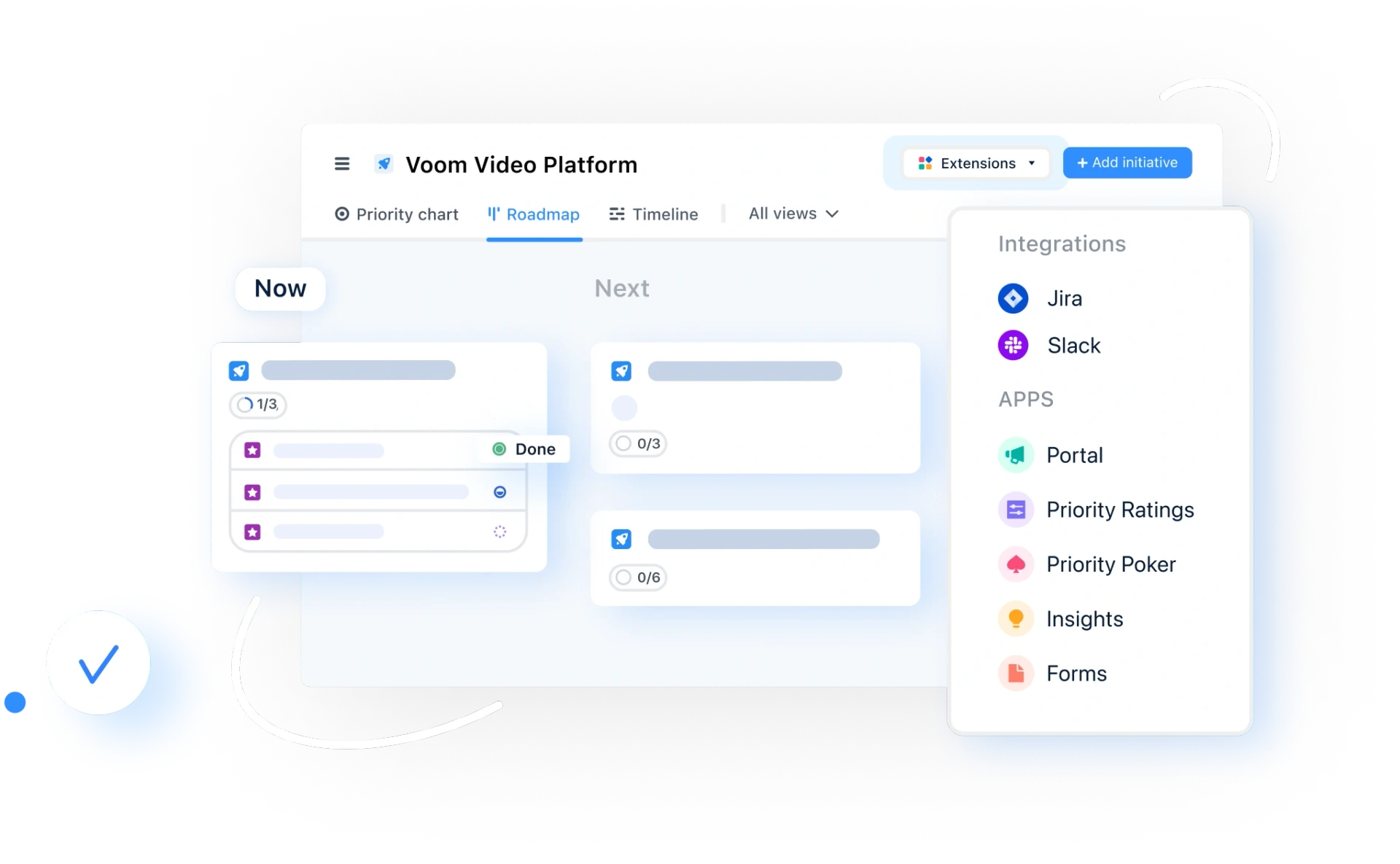

Experience the new way of doing product management

Experience the new way of doing product management