Technical Debt

What is technical debt?

Definition of technical debt

Also known as "design debt", "code debt", or "tech debt", the definition of technical debt is when a development team opts for a faster but compromised solution to a problem compared to a slower but more comprehensive one, and the resultant cost of the later reworking of the product, in terms of resources and time.

The concept should be thought of in the same way as monetary debt, as, not servicing it can cause it to accrue "interest". In this sense, the interest created by the technical debt will impact other aspects of the project - especially as it develops - and therefore can be considered to have accrued.

The term is also used as a broader means by which to describe things like "bugs", legacy code, absent documents, and a host of other issues that can creep into a product development project.

Technical debt origin.

The term originates with Ward Cunningham, a software developer and one of the 17 authors of the agile manifesto. He also invented the framework for integrated tests and is a pioneer in design patterns and eXtreme programming. It should be noted that over time and with great debate, the definition of technical debt has not remained clear. Some commentators take the view that the debt is messy and should be avoided, compared to others that express the notion that accruing the debt can be a useful and deliberate tool.

What causes technical debt?

There are various factors that might cause a development team to actively decide to incur the debt, or, indeed, incur it accidentally.

Design lag This is where the development of the product begins in earnest before any design has been started. This normally occurs as a result of deliberate decision-making.

Market pressures This can occur when a need has arisen to get the product to market faster than planned. Features may not be properly completed or installed or changes not be finished. Usually, this is a considered decision.

Collaboration deficit Failure to share knowledge across the business means any number of problems can arise to cause debt later. A very common type of debt that is inadvertent.

Knowledge gaps Sometimes a business might make decisions without the requisite knowledge and end up making mistakes as a result, increasing technical debt. Corrections requiring various resources later might be needed. Or, perhaps, a developer lacks the knowledge to write graceful code causing unforeseen complications later. Or further still, outsourced work is found to be substandard and requires reworking further down the line. All of these are characterized as inadvertent types of debt.

Circumventing industry standards Deciding not to integrate industry standards in design, frameworks, or technologies until later can incur debt. Unless there is a significant knowledge gap in the business, this is more likely to be a conscious decision rather than an error.

Specification alterations Where last-minute changes have been made to product specifications, a business might be unable to fully generate documentation or undertake inspections that need attention later. It is possible this can be an inadvertent or deliberate form of debt - an organization may be simply unable to address the problem in a timely fashion or may choose to prioritize other work and decide to incur the debt.

Inadequate direction Instructions that lack due consideration from leaders or managers can filter down a business hierarchy. Action taken based on those instructions can be in error leading to inevitable technical debt further into the product development cycle. This debt is inadvertent.

Etc, etc, etc. There is a profusion of ways in which debt can materialize. Some other ways: product development might lack the flexibility to change paths or reprioritize tasks when business needs evolve; lack of controlled testing giving rise to hasty bug fixes that then need later attention; lack of foresight on work being carried out on parallel aspects of the product that require to be merged later but cannot.

Different forms of debt

As previously mentioned, there has been a substantial wider debate about accumulating technical debt within the industry. And whether or not debt in a business is calculated or unwitting, it has been classified by the software engineering Institute into 13 different forms. These are architecture, build, code, defect, design, documentation, infrastructure, people, process, requirement, service, test automation, and test.

Their classification is in contrast to the technical debt quadrant devised by Martin Fowler. His schematic shows a grid where the technical debt of a business can be either deliberate or inadvertent, and either reckless or prudent.

His system makes it possible for a debt to be any of four combinations: "inadvertently prudent", "deliberately reckless" etc. The institute has dismissed Fowler’s system.

Accruing interest on debt

Whether or not technical debt has been accrued by a business through decision-making or mistake, the theory suggests it is possible for the debt to escalate through amassing interest. Interest can be seen as the "knock-on" effect of the original debt.

For example, if code has been inelegantly created at the base level of the product, resulting in features later in the project that may need to accommodate that code.

Consequently, the code of the feature will be directly impacted. To return to the original programming and amend it, work will also have to be carried out on the feature’s code too. In this way, if the debt is neglected for longer, other areas of the product may need to accommodate the original code and be revisited in turn.

As the development cycle progresses, and the original debt remains unresolved, in this way, the debt increases and can be referred to as "interest".

Good or bad

Technical debt is not really considered good or bad, much like financial debt. Without it, businesses in the modern software industry would be far more unwieldy. Startups, in particular, need to be operationally dexterous to remain relevant and successful and can use the trade-off to great effect: an earlier product launch with some technical debt in the toe can keep the business competitive.

Striking a reasonable balance between benefits and debt is imperative. Accruing large amounts of inadvertent technical debt in a product might be considered indicative of fundamental problems lurking behind a business, whereas utilizing discrete amounts of deliberate technical debt in the right way can be a great boon to an organization.

General FAQ

Glossary categories

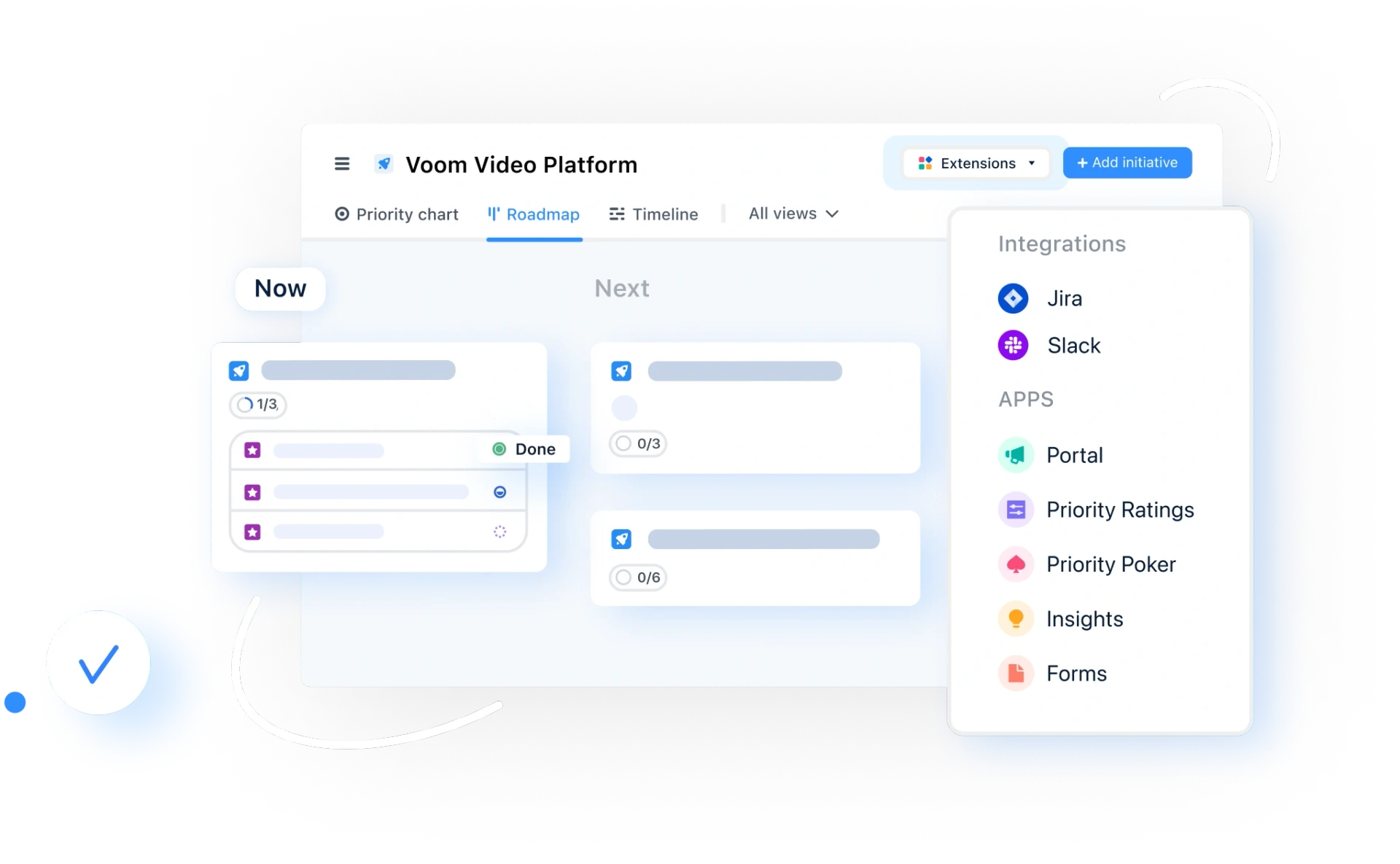

Experience the new way of doing product management

Experience the new way of doing product management